- After Tsar Nicholas II was overthrown in February 1917, the Russian Empire collapsed and followed a path through Marxism, Leninism, and Communism to the Cold War until the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991. Stop and think, for a moment, of the economic and social changes that took place in Russia under leaders like Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev, and Putin.

- Japan entered World War I and World War II as a ruthless aggressor. After the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan's rebirth was nothing less than an economic miracle. Its subsequent ups and downs have rattled stock markets around the world.

- Germany transitioned from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich; from postwar division into East Germany and West Germany to its 1990 reunification. Today, it is once again a world leader.

- Who would ever have believed that so many nations would join together to form a European Economic Community under one currency?

- Or that the Middle East would undergo so many years of conflict?

- Gone are the days of the British Raj, the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Indira Gandhi. Today's India has emerged as a superpower.

- Gone is South Africa's loathsome policy of apartheid.

In the first half of the 20th century, the fascination with Orientalism ranged from speculation about opium dens to 1917's ragtime hit by Lee S. Roberts and J. Will Callahan.

- Caucasian audiences took great delight in the exploits of Charlie Chan, a character created by Earl Der Biggers, a writer who (surrounded by hysterical fear of the so-called Yellow Peril) stated that "Sinister and wicked Chinese are old stuff, but an amiable Chinese on the side of law and order has never been used."

- In 1967, Beatrice Lillie was cast as the predatory Mrs. Meers in Thoroughly Modern Millie, (portraying the Chinese house mother of the Priscilla Hotel for single women who, unbeknownst to her naive clientele, was selling her orphaned tenants into white slavery through the Chinese men who handled the hotel's laundry).

- In 2008, Lauren Yee's Asian-American farce, Ching Chong Chinaman, received its world premiere from Impact Theatre in Berkeley. Its plot summary reads as follows:

"The ultra-assimilated Wong family is as Chinese-American as apple pie: teenager Upton dreams of World of Warcraft superstardom; his sister Desi dreams of early admission to Princeton. Unfortunately, Upton’s chores and homework get in the way of his 24/7 videogaming, and Desi’s math grades don’t fit the Asian-American stereotype. Then Upton comes up with a novel solution for both problems: he acquires a Chinese indentured servant, who harbors an American dream of his own."

|

| Poster art for Ching Chong Chinaman |

The recent A Day of Silents minifestival presented by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival featured two programs which offered remarkable views of China (and Chinese people abroad) as seen through Western eyes. Although one was fiction and the other nonfiction, the element of Chinese exoticism was at the core of each presentation.

* * * * * * * * *

In recent years, the British Film Institute has been digitizing footage from documentaries, home movies, travelogues, newsreels, and missionary films recorded in China between 1900 and 1948. Accompanied by Donald Sosin on piano, these clips ranged from the mundane to the fascinating. The following slide show (which was screened prior to the one program at the Castro Theatre) offers glimpses into China's past.Around China With A Movie Camera: A Journey From Beijing To Shanghai (1900-1948) offered the audience a chance to travel back in time to a period when there were far fever people living in China than its current estimated population of more than 1.37 billion.

The films are remarkable for their diversity, capturing scenes in rural communities, along the Great Wall of China, as well as boat traffic on the Yangtze River. All kinds of transportation (from men carrying sedan chairs in Hong Kong to coolies pulling rickshaws through city streets) are on view. According to the program notes from the British Film Institute:

"Highlights include Shanghai’s bustling, cosmopolitan Nanjing Road in 1900, the Great World Amusement Park in 1929 and a day at the Shanghai races in 1937. Films of the streets around the Qianmen, Beijing, in 1910, Hangzhou’s picturesque canals seen in 1925 and early-20th-century views of big city glamour in Hong Kong, Chongqing, Guangzhou, and Kunming compete with scenes captured in remote villages in Hunan and Yunnan provinces offering a dazzling and unprecedented view of China at a key period in its history. One of the most fascinating items in the collection are the only known home movies from the 1930s made by a Chinese British family (Mr. S.K. Eng) who recorded an extensive holiday visit to China in 1933 including scenes from Shanghai where he had received his education."

| A scene from Around China With A Movie Camera: A Journey From Beijing To Shanghai (1900-1948) |

While the poverty is often inescapable, these clips offer color-tinted views of celebratory processions, street markets, and fishing with cormorants as well as footage of Indian and German military officers walking down a street. From smaller communities like Suzhou and Kunming to major cities, the clips offer a wonderful experience in time travel. From scenes in a stilted city (Chongqing) to the canals of Hangzhou (billed as an Oriental Venice); from the Forbidden City to scenes of children practicing acrobatic tricks, these short films (many of which can be viewed at the BFI's website by clicking here) offer glimpses of China that have rarely been seen.

* * * * * * * * *

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival concluded A Day of Silents with a screening of 1929's Piccadilly, directed E.A. Dupont and starring the great Anna May Wong as Shosho, the scullery worker at a nightclub who is first seen dancing on a table for the kitchen staff before she rises to become the club's star attraction.While Piccadilly's plot is filled with betrayal and backstabbing, it also shows a keen awareness of the tensions caused when people of different races try to socialize together. Not only is Shosho blamed by Mabel Greenfield (Gilda Gray) for stealing her lover, Valentine Wilmot (Jameson Thomas) -- who is the owner of the Piccadilly Club -- in the sequence when Shosho and Valentine visit a dive bar, they witness what happens when a drunken white woman attempts to dance with a black man.

Beautifully directed, the film features a young Cyril Ritchard as Mabel's dancing partner (Victor Smiles) and the screen debut of Charles Laughton as a picky diner who is incensed at being handed a dirty plate. The following clip shows Gilda Gray reacting to the distraction caused by Laughton's character while she is performing her dance routine with Cyril Ritchard.

In her program note, Imogen Sara Smith writes:

"Like Josephine Baker and Louise Brooks, Anna May Wong was an American woman who had to cross the Atlantic to find her greatest roles. In Piccadilly, Wong seems to be sporting Brooks’s bangs and Baker’s sinuous hips, but her knowing look -- wary, sultry, and intense -- is all her own. Her entrance is a knockout: in the bowels of a London nightclub, amid the steamy chaos of the scullery, she is dancing on top of a table for the amusement of her fellow dishwashers. Peering up at her, the camera lingers on her stunningly long and shapely legs, clad in stockings 'laddered' (as the British say) almost to shreds. Her swaying hips are all the more mischievous and provocative because it is obvious that this Chinese scullery girl is mimicking and mocking the nightclub’s blonde star dancer. Dance is not harmless entertainment: it is dangerous, seductive, rule-breaking."

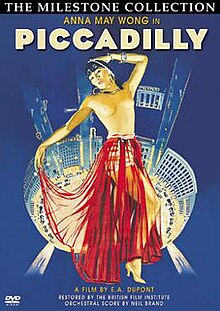

|

| Poster art for Piccadilly (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons) |

With Donald Sosin accompanying the screening on piano, two supporting actors delivered fine work: Hannah Jones (a great character actress) as Shosho's friend and dishwashing supervisor, and King Hou Chang as Shosho's lover, Jim.

| Anna May Wong as Shosho and King Hou Chang as Jim in a tense scene from 1929's Piccadilly |

An interesting piece of trivia from Wikipedia reveals that, in the scene where Shosho is hired to become the Piccadilly Club's star, "Anna May Wong (as Shosho) signs her contract with the characters 黃柳霜, which is actually her real Chinese name, Huáng Liǔshuāng." Here's the trailer:

No comments:

Post a Comment