When not actively engaged in competitive situations (auditions, talent shows), much of a creative person's integrity involves competing against themselves. In the long run, artists are the ones who will gain the most from improving the how and why of what they do. Whether they inspire others to rise to their level (or are challenged to reach higher by their colleagues), their artistic goals can usually be described as "onward and upward."

Two recent dramatic experiences placed struggling artists front and center. In one effort, a documentary film followed a handful of artists hoping to win a major competition. In the other, a well-established actor with a unique backstory and set of artistic tools was challenged to work with people who blatantly scorned him, distrusted his qualifications, and did everything they possibly could to deny him a role for which he was eminently qualified. One story focused on a willingness to accept all participants; the other showed what can happen when racism triumphs over professionalism.

* * * * * * * * *

Early this year, the media was filled with news about the illegal occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Harney County, Oregon. While many people agonized over this story and the damage its participants did to part of a critical flyway for migrating birds, I sincerely doubt that anyone sought a connection to a story about wild ducks.Except, perhaps, for Brian Golden Davis, the director of a delightful new documentary entitled The Million Dollar Duck which had its world premiere at the 2016 Slamdance Film Festival and will be screened next month at SF DocFest. Davis's film has no relationship to Donald Duck or any other Disney franchise. Instead, it tells the story of the only art competition that is mandated by the federal government.

|

| Designed by Jay Darling, the first United States duck stamp was issued on August 14 1934 (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons) |

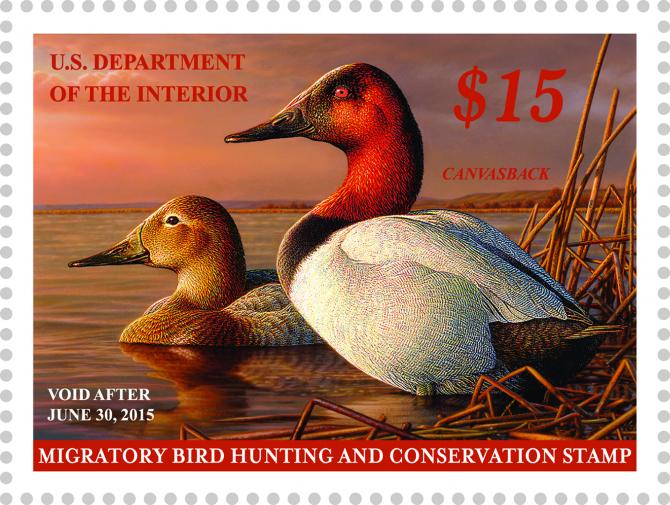

In 1929, President Herbert Hoover signed the Migratory Bird Conservation Act, which authorized the acquisition and preservation of wetlands as waterfowl habitat. The Federal Duck Stamp program was launched by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who signed the 1934 Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act into law. According to Wikipedia, that act created a stamp which was "required by the United States federal government to hunt migratory waterfowl such as ducks and geese. It has also been used to gain entrance to National Wildlife Refuges that normally charge for admission."

Because 98% of the proceeds of each sale of duck stamps go to the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund. this unique arts program has raised more than $850 million to acquire six million acres of wildlife habitat. As Mark Anderson (who won the 2004 Federal Duck Stamp competition) explains: "In music you have the Grammys. If you're an actor, it's the Oscars. If you're a wildlife artist, it's winning the Federal Duck Stamp contest."

| The winning 2015-2016 Federal Duck Stamp featured ruddy ducks and was painted by Jennifer Miller |

Like many documentaries about competitions, Davis follows a handful of artists who have decided to enter the Federal Duck Stamp competition. Each year, the species of ducks to be used in this juried competition is announced by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Artists are free to draw ducks in whatever pose they desire. Each artist must submit a painting measuring 7x10 inches which will be judged for its technique, accuracy, and artistry. While no financial prize is attached to the competition, the prizewinner can license his image as creatively as possible, whether selling the rights for prints, calendars, coffee mugs, etc.

|

| Adam Grimm's painting of canvasback ducks was the prizewinner in the 2013 Federal Duck Stamp contest |

Among the contestants who appear in Davis's documentary are prizewinner Adam Grimm from Eureka, South Dakota and his close friend, Tim Taylor. The July-August 2014 issue of Audubon Magazine featured a delightful cover story about the two men entitled Duck Dynasty.

Between them, the three Hautman brothers from Minnesota (Jim, Joe, and Robert) have won the Federal Duck Stamp contest ten times. Rebekah Nastav of Appleton City, Missouri is a postal worker who delivers mail in a rural area. Dee Dee Murry is a wildlife painter in Centralia, Washington who has taken to selling paintings made by her blind dog (who sometimes brings in more money over the Internet than she does).

However, it is Rob McBroom of Minneapolis (who calls his style "lowbrow surrealist"), who is acknowledged by most participants as the good-natured class clown of each year's competition. McBroom makes no apologies for his use of rhinestones, glitter, corporate logos, and glow-in-the-dark paint in his entries (the falling raindrops depicted in one of his paintings included the Morse code translation of a porno monologue).

|

| Three of Rob McBroom's duck paintings |

Without doubt, The Million Dollar Duck benefits immensely from Christian Bruno's cinematography. Whether following Grimm and Taylor as they float duck decoys in rural waters or showcasing McBroom's merrily subversive art, this documentary will have plenty of appeal for birders, wildlife enthusiasts, and members of the National Duck Stamp Collectors Society as well as those who, like myself, grew up with a set of John James Audubon's famous lithographs in their home.

* * * * * * * * *

Cultural appropriation has recently become a hot topic in theatre. With Asian American groups hot under the collar about Hollywood's preference for casting Caucasian actors to play Asian characters in yellowface -- and chastising small opera companies for scheduling productions of Gilbert & Sullivan's 1885 comic opera, The Mikado -- it's important to remember that, in the opera world, voice trumps skin color.While nobody ever questioned the tradition of Caucasian opera singers donning blackface to sing the roles of Aida (an Ethiopian princess) or Otello (a Moor), Leontyne Price startled the opera world when she began to portray Aida in major opera houses. On several occasions, the make-up artists did not know what kind of make-up to use on her skin. As she explains:

"Let's start with the obvious, or what seems like the obvious. Aida is a black woman and, in the world of opera, black artists don't have many opportunities to play black characters. That's it on a very simplistic level. But it goes far beyond that. I was always totally at ease when I sang the immortal phrases composed by that great master, Giuseppe Verdi, for his enslaved princess."

"I used to joke that when a theatre cast me as Aida they could always expect to save on make-up. (It's not that I didn't wear any makeup as Aida; every artist wears makeup on stage. But, as Aida, I can assure you, I could get away with less than just about any of my colleagues!) It was a joke, but there was a serious statement lurking behind my attempt at humor: When I performed Aida, the color of my skin became my costume, and that gave me an incredible freedom no other role could provide. My skin was my costume -- all I had to do was drape something over it."In 2015, the Metropolitan Opera announced that in its new production of Verdi's Otello, the tenor singing the title role would not use blackface for the first time since the Met presented Otello in 1891. The Met's statement read as follows:

"Although the central character in Otello is a Moor from North Africa, the Met is committed to color-blind casting, which allows the best singers possible to perform any role, regardless of their racial background. Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko is among a small handful of international dramatic tenors who can meet the considerable musical challenges of the role of Otello, one of the most demanding in the entire operatic canon, when sung without amplification on the stage of the world's largest opera house. In recent seasons, Antonenko has sung the role to acclaim at the Royal Opera in London, at the Paris Opera, and with Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, and we look forward to his first performances of the role at the Met in

Bartlett Sher's season-opening new production. Antonenko will not wear dark makeup in the Met's production."

The San Francisco Playhouse recently presented the West Coast premiere of Lolita Chakrabarti's historical dramedy, Red Velvet, in a handsome production with costumes by Abra Berman and scenery and projections designed by Gary English. The play's protagonist is the 19th-century actor, Ira Aldridge (who performed throughout Europe and is the only African-American actor honored with a bronze plaque on the walls of Stratford-upon-Avon's historical Shakespeare Memorial Theatre).

| Carl Lumbly as Ira Aldridge in Red Velvet (Photo by: Ken Levin) |

The play begins in 1867 in the dressing room of a theatre in Lodz, Poland, where an aging Aldridge's fiercely protected privacy has been breached by an aspiring journalist named Halina Wozniak (Elena Wright), who has won the favor of the stage manager (Devin O'Brien). Despite her fractured English, Halina manages to resurrect disturbing memories of Aldridge's 1833 experience in London when his friend, Pierre LaPorte (Patrick Russell) managed to get him a booking as a replacement for the ailing actor, Edmund Kean, in the title role of Shakespeare's Othello.

Nearly 200 years ago, the substitution of a dark-skinned actor to play a famously dark-skinned role was nothing less than scandalous. Kean's untalented son, Charles (Tim Kniffin) is emphatically opposed to the substitution, as is a rather stodgy actor named Bernard Warde (Robert Louis James). Only Ellen Tree (Susi Damilano) is willing to give Aldridge a chance. Not only is Ellen the company's leading lady, she is also Charles's fiancée.

| Susi Damilano as Ellen Tree in Red Velvet (Photo by: Ken Levin) |

While others seem repulsed by the idea of working with an African-American actor (and can barely hide their disgust at the idea), Ellen's fascination with Aldridge is not just because of the color of his skin. Up until this point, Kean's acting company has been relying on the "teapot" style of acting which, when confronted with a more realistic approach to drama, seems archaic and slightly silly.

An experienced Shakespearean who has toured the Continent, Aldridge represents a more natural style of acting, in which performers actually face each other when speaking to one another. Yet there can be no denying the simple fact that the mere presence of this handsome and charismatic dark-skinned man brings a presence to the stage which can simultaneously be threatening to the men and titillating to the women. Damilano's nervous excitement and obvious fascination are a delight to behold.

| Carl Lumbly, Patrick Russell, and Devin O'Brien in a scene from Red Velvet (Photo by: Ken Levin) |

Because the story unfolds against the backdrop of England's abolition movement, it has many parallels to America following the Emancipation Proclamation (as well as the current scourge of "Obama derangement syndrome"). By the time Aldridge is fired from appearing as Othello, it becomes obvious that his effect on Lady Ellen was far less erotic than exotic; much less sexual than professional.

Towering over the evening is the powerful performance of Carl Lumbly as Aldridge, a celebrated actor who suddenly finds himself accused of molesting his Desdemona simply because Lady Ellen came to his dressing room to discuss things they might do during the next performance. When Aldridge is betrayed by LaPorte (who may also have been his male lover) and the production shut down rather than let performances of Othello continue with an African American actor playing the title role, the humiliation is crushing. To make matters worse, Aldridge had just purchased a home in which he hoped to settle down with his wife, Margaret (also played by Elena Wright).

| San Francisco Playhouse's cast of Red Velvet (Photo by: Ken Levin) |

The production has been beautifully directed by Margo Hall, with great care to show the silliness of the teapot style of acting, the abject racism of Lady Ellen's colleagues, and the fierce resistance to change. Britney Frazier has a key scene as Connie, the company's black maid who is reluctant to let Aldridge see the scathing reviews of his performance. Credit is also due to Theodore J. H. Hulsker for his work as sound designer, projections engineer, and assistant projection designer.

| Britney Frazier and Carl Lumbly in a scene from Red Velvet (Photo by: Ken Levin) |

Performances of Red Velvet continue through June 25 at the San Francisco Playhouse (click here for tickets).

No comments:

Post a Comment